A few weeks ago, my wife and I went to see the movie The Brutalist. The extent of the hype for this movie was truly breathtaking, which may be partly why I was not surprised that it did not live up to its “promise”.

I must admit that media coverage led me to question whether those who were singing its praises even understood anything about the movie’s subject matter! For example, a fawning item about it on ABC News included paroxysms of praise for the movie’s stars and director, but never actually mentioned what the movie is about, nor was there any explanation of what the title “Brutalist” referred to! I guessed that it must have something to do with Brutalist Architecture, and it turned out that I was correct, but that was no thanks to ABC. Did the presenters really not understand it themselves, or had they decided that the explanation was too “intellectual” for their audience?

Perhaps that is, in fact, the key to the praise that the movie has received. It seems that the less a reviewer knows about its subject, the more they like the movie. Those who do understand its subject matter, professional architects, have been highly critical of its blunders and implausibility, to the extent that they are described as “hating” it in this article.

I also thought that, given its thin, questionable plot and appalling examples of ignorance, the movie was much too long at 3 hours, 35 minutes. As the Guardian reviewer states sarcastically:

“The architecture world awaits with bated breath the director’s five-hour marathons, The Postmodernist, The Deconstructivist, and The Parametricist – each to be shot with period-appropriate equipment and based on a brief skim through a coffee-table book”

Personally, the only benefit that I obtained from the movie experience was that it prompted me to think once again about the real Brutalist architecture that I grew up in and around, the history of which I find infinitely more interesting than any aspect of the movie.

Growing up, Brutalist architecture was a constant background theme in my life, and I even lived in one example of it for a while.

Brutal Aylesbury

I never actually lived in the Buckinghamshire county town of Aylesbury, but, as I recounted in a previous post, my first visit there involved a job interview and a “computer programming aptitude test” that had a profound effect on my view of my own abilities in that field.

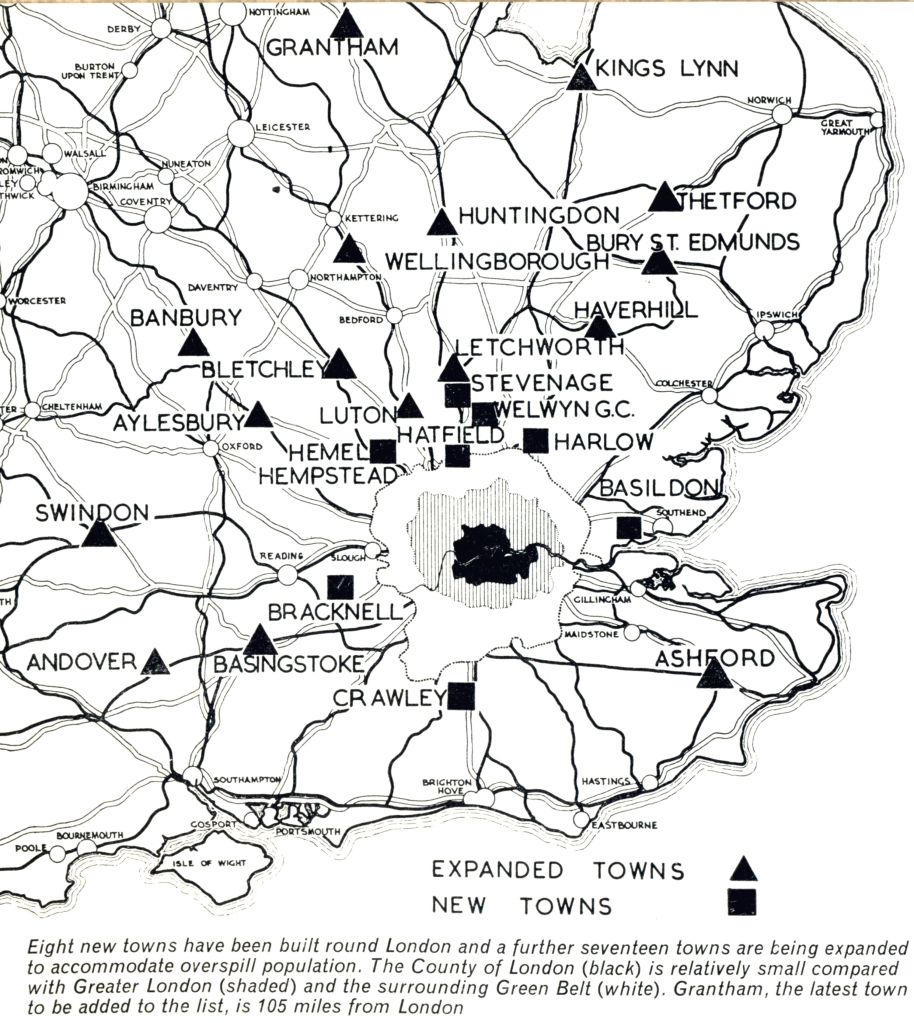

During the period from the 1930s to the 1970s, the British Government made major investments in a group of what were referred to as London Overspill Towns. There was a deliberate policy of moving population en masse out of London, to more rural locations. The goal was mainly to reduce further “ribbon development” of the London suburbs, which would eventually have spread across the entire South-East of England. There were also health implications, since prior to the 1960s, London’s air was seriously polluted, leading to increased healthcare costs.

During the 1960s, various existing towns were targeted for substantial redevelopment and expansion, and a few entirely new towns were created. Most of these were within commuting distance of London, but even Grantham in the East Midlands was included.

The map below is from the 1963 book New Architecture of London.

As shown, one of the “expansion towns” was Aylesbury, which had until then been a quaint market town, famous mostly for its ducks.

Development plans for expansion towns invariably included the construction of new shopping centers and civic buildings, and some of these were designed along brutalist architectural lines. In 1967, Aylesbury found itself lumbered with a new shopping center, Friars Square, which quickly came to be seen as such an outstanding example of a dystopian nightmare environment that, in 1971, scenes for the movie Clockwork Orange were filmed there!

My 1980 photo below shows the centerpiece of Friars Square, the Cadena Cafe, after it had become a Wimpy Bar. As with many examples of brutalism, the building had a relatively short life, being demolished in 1993 when the shopping center was redeveloped.

Elain Harwood’s book Brutalist Britain offers an extensive listing of brutalist architecture in the country, and describes another Aylesbury example, the Buckinghamshire County Council office tower.

My 1980 photo below shows the County Council tower looming above Market Square in Aylesbury, with the Bell Hotel in the foreground.

Brutal Birmingham

It seems perhaps most appropriate that Brutalist architecture would be chosen for the design of industrial buildings, and even British Railways constructed a few examples. One of the most famous in Britain must surely be Birmingham New Street Signal Box, which has towered above the gloomy subterranean station since 1966, and is clearly visible from street level, as shown in my 1980 photo above. Although it closed as a signal box in 2022, the building is listed, is still standing, and continues to be used by Network Rail.

Again, Birmingham was not a city in which I ever lived, but when traveling between Coventry and York, I usually had to change trains at Birmingham New Street. I also applied to, and was accepted by, Aston University in Birmingham, so I attended an interview there in 1980.

Brutal London

Approximately a year after visiting Aylesbury for that job interview, I found myself moving to London, as I began my Electronic Engineering studies at Imperial College.

Many first-year undergraduate students were accommodated in Halls of Residence, situated in South Kensington near the college campus. Generally, we were assigned to one of the halls, and were not given any option as to which hall we preferred. I was assigned a single-bed room in Selkirk Hall, which was a subdivision of the huge Southside Halls building, located, as the name indicates, on the south side of Prince’s Gardens.

The photo at the head of this article shows the view looking north from Selkirk Hall over Princes Gardens, one stormy afternoon. The building in the foreground is Linstead Hall, which was of similar architectural style to Southside. In the distance, the tower of another Brutalist edifice is visible; Hyde Park Barracks, which was and still is the home of the Horse Guards.

Unfortunately, while living in Selkirk Hall, I never photographed the outside of the building itself (partly because the trees in front of it obscured most of it). However, Owen Hopkins’ book Lost Futures includes an article about Southside Halls, which also mentions the smaller Weeks Hall, situated on the north side of Prince’s Gardens.

The photo below, borrowed from “Lost Futures”, shows an excellent panorama of Southside, before the trees in front of it grew too large.

Unfortunately (or perhaps fortunately, depending on your view of their aesthetics!), the passage of time has revealed that many Brutalist buildings were not well-constructed, and in some cases not even well-designed. I had personal experience of this while living in Selkirk Hall.

I lived in the building for only one academic year, but even during that time there were serious maintenance problems. Each bedroom had its own sink, whereas kitchen and bath facilities were shared. The sink in my room was out-of-action, and boarded off, for several weeks during my residency, due to plumbing problems. It seems that the design of the building had a major flaw, whereby pipes and other service conduits were buried directly within the concrete, instead of being placed in accessible service ducts. As a result, any plumbing maintenance work required drilling out the concrete to access the pipes! The quality of the concrete also seems to have been defective, and large chunks of it eventually began to disintegrate.

The upkeep of Southside became so problematic that, despite its being a listed building, permission was eventually granted to demolish it in 2005. That permission was granted on condition that the smaller Weeks Hall, on the north side of Prince’s Gardens, and also a listed building, be retained and refurbished. In my photo below, looking north from Southside, you can just see Weeks Hall towards the right.

One of the more successful examples of Brutalist architecture, which still exists and is in use today, is the Barbican Centre, in the City of London. My photo below shows part of the complex shortly after its official opening in 1982. I visited the Centre many times, usually to go to the Museum of London, which was housed within it.

Despite having been voted the “Ugliest Building in London”, the Barbican apparently remains popular with apartment renters, thanks to its views and convenient location.

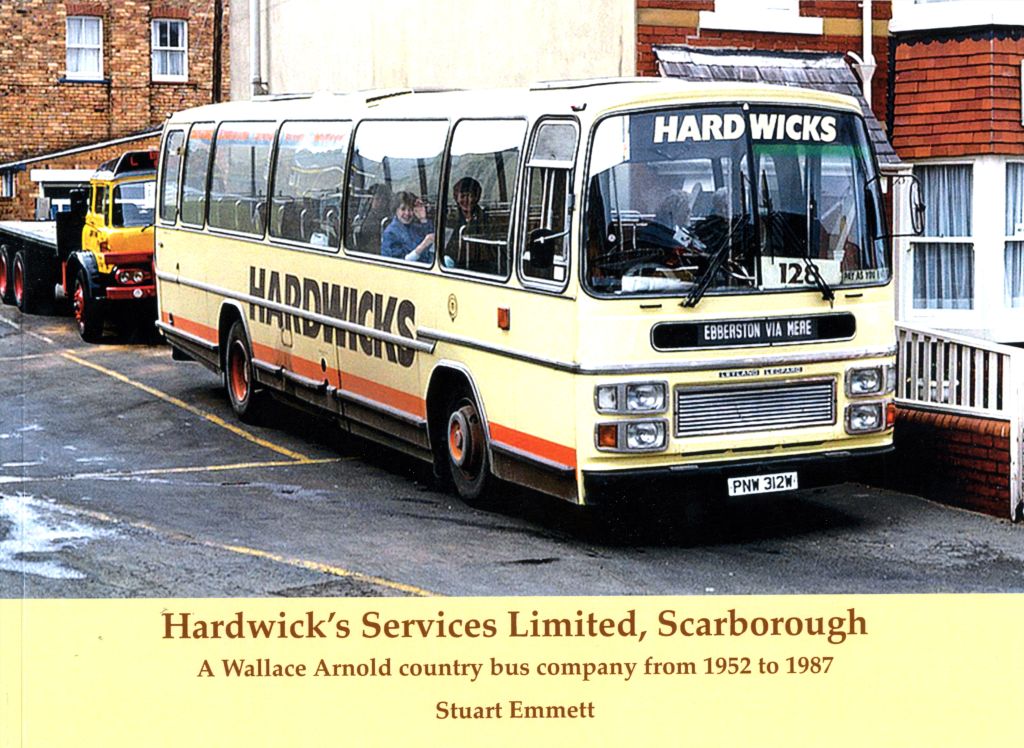

Brutal Scarborough

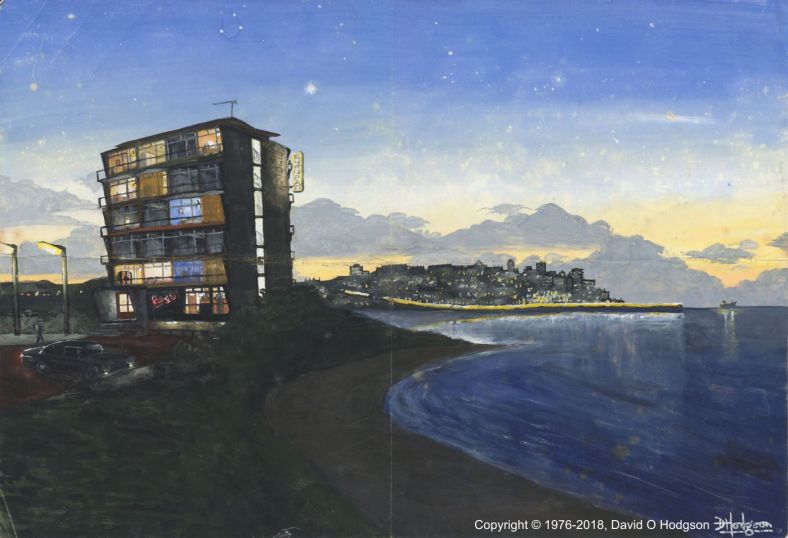

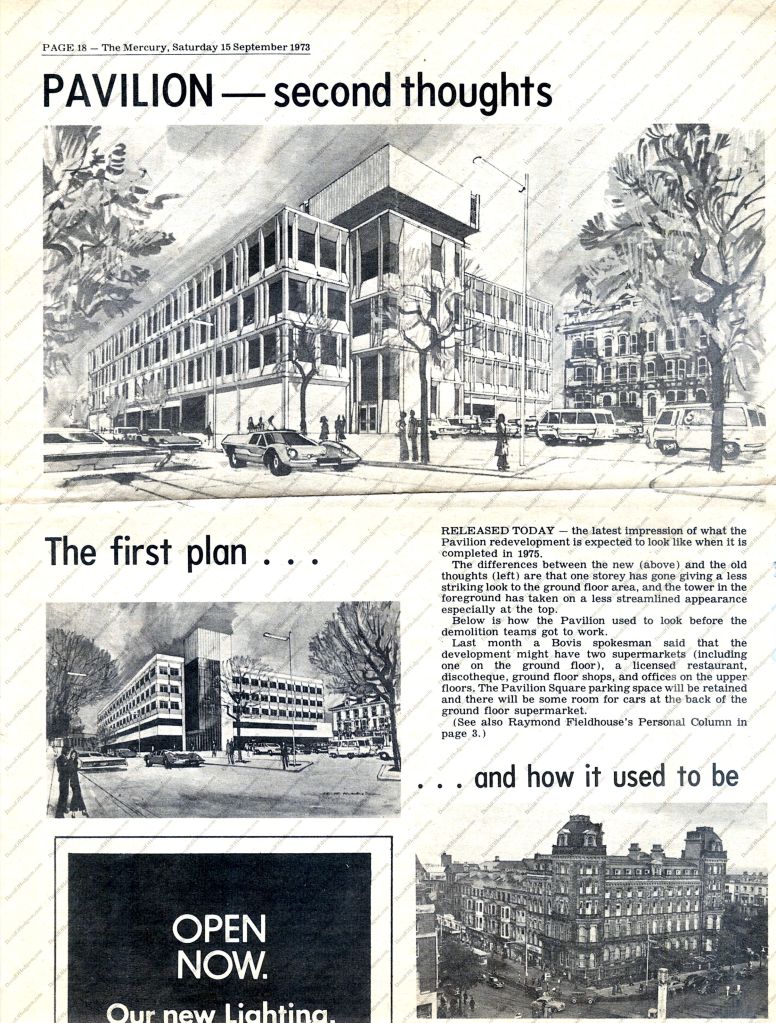

Even my home town of Scarborough suffered the attentions of architects with brutalist leanings. In 1973, the imposing Pavilion Hotel, immediately opposite the main railway station, was controversially demolished and eventually replaced by an office block that has been described as the “ugliest building in Scarborough”. I reproduce below an article from the Scarborough Mercury of 15th September 1973, showing how the new building was to look, along with hopelessly-optimistic predictions of its future uses.

The building did eventually gain one supermarket, on the ground floor, although, as I recall, that store managed to look run-down from the day it was opened! As regards actual other uses for the new building, I can only remember it as the home of Scarborough Job Centre, in which I spent many useless hours not finding a worthwhile job. It seems perhaps appropriate; a depressing and ugly location for a depressing and hopeless office!

There’s no question that, whatever the aesthetic qualities of those Brutalist buildings, they were and are each unique, and they formed a memorable backdrop to my life in those days.

![South Elevation of Broadcasting House, from the book "London Deco", by Thibaud Hérem[20]. Copyright © 2013 Nobrow Press](https://davidohodgson.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/broadcastinghouse-1.jpg)