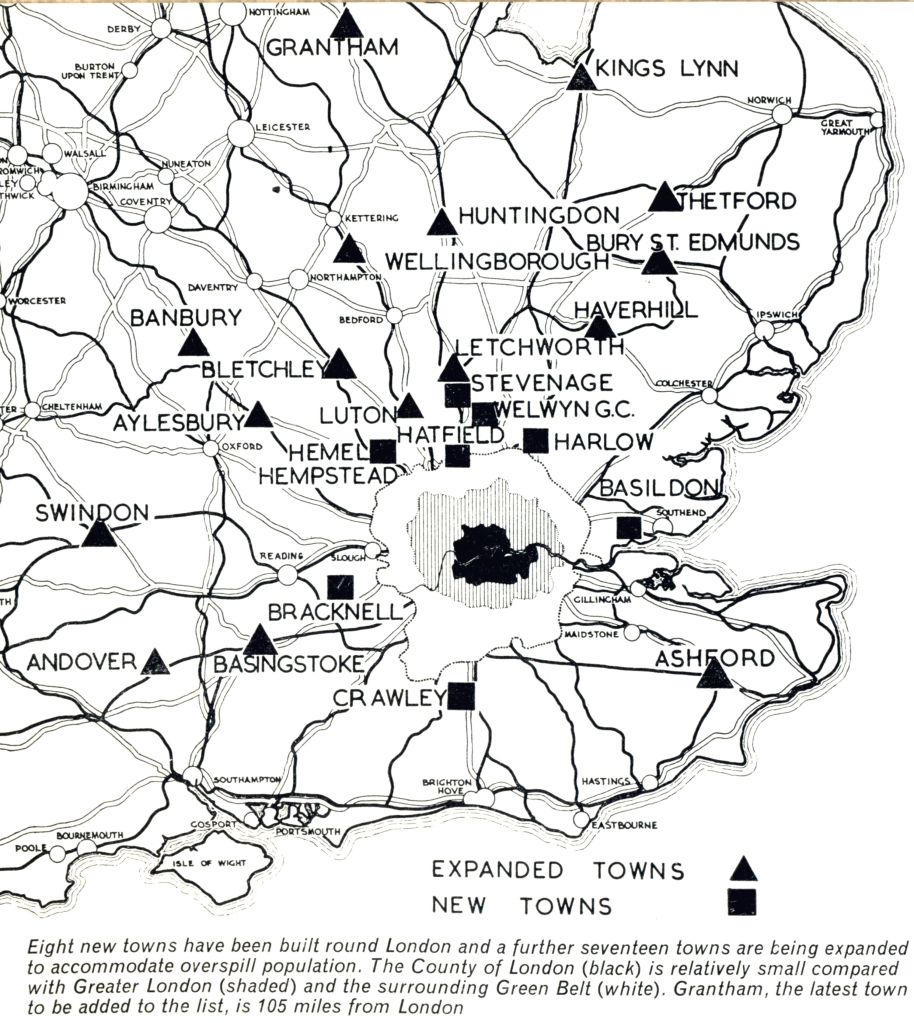

BBC Broadcasting House, from Portland Place

The photo above is, sadly, the only one that I ever took of BBC Broadcasting House, even though I worked there and walked in and out of the building regularly. With the benefit of 40 years of hindsight, I regret that, from 1984 through 1987, I took no photographs at all. At that time, it simply never occurred to me that I might one day want to describe and illustrate what was happening to me! I was only prompted to restart taking photographs when I visited California for a job interview in October, 1987. Therefore, this article, and others discussing the events of this time period, are unfortunately quite lacking in personalized images!

In a previous post, I mentioned how, during the early 1980s, my primary goal in obtaining an Electronics degree had been to obtain what I sincerely thought would be my “dream job”, as a video engineer at the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). I finally obtained that job in 1984, almost exactly 40 years ago, so this seems like an appropriate time to review the details of what happened then, and my reactions to it.

Having completed my degree at Imperial College, London, I interviewed for and obtained an entry-level Engineering job with BBC Studio Capital Projects Department (SCPD), which was responsible for building and renovating studios. The final interview seemed to go so well that I actually had the temerity to ask the intimidating board of three interviewers about my chances, given that I’d already received a job offer from the Philips television systems design plant in Croydon (which I did not want to lose, if the BBC turned me down again).

The interview board asked me to leave the room for a few minutes while they discussed my case. When I re-entered the room, they informed me that, subject to their receiving confirmation of my degree grade, I’d got the job! The only further thing they wanted to know from me was, “how come you know so much about television?” I explained that I’d just spent the last 2 years as a volunteer and then Chairman of Imperial College Student Television, which had given me experience in every production job, from producing through presenting to videotape editing.

Now, with the benefit of so much hindsight, I see that I should perhaps have been tipped off by that final question that something was amiss, but, after all, in those days I was just a naïve young graduate, who naturally trusted that my new employer would be acting in my best interests!

Letter from the BBC, informing me that I’d been selected

I was overjoyed at being offered the opportunity that I had sought for so long, but unfortunately I was soon to discover that the reality of my new job was not at all what I’d anticipated.

Digression: The Realities of Auntie

For readers who do not live in Britain, I should perhaps explain something about the exalted status of the BBC (nicknamed “Auntie”) in that country’s national mindset. (This reputation has been seriously damaged by recent scandals, including official cover-ups of abusive and pedophile behavior by certain BBC celebrities, but, back in those days, that was all kept firmly secret.)

It may come as a surprise to you to learn that, in a country that is supposedly a cradle of free speech, the BBC was for many decades a monopoly broadcaster in Britain. For many decades, by law, only the BBC could broadcast radio or television services. As from 1923, all British residents had to pay an annual licence fee to operate broadcast reception equipment, although since 1971, only television receivers have required a licence. Any other organization that attempted to broadcast was a “pirate”, and the British government made strenuous efforts to shut down such organizations whenever they could. Nonetheless, broadcast advertising was such a lucrative market that many pirate radio stations did operate. As I recounted in a previous post, the governor of my own school was a director of one such pirate station!

Despite its monopoly, the BBC was not officially an arm of government. It was nominally independent, and, although it usually toed the government line, its independence was sometimes the cause of friction between the Corporation and officialdom.

The BBC lost its monopoly on television broadcasting in 1955, when the Independent Television Authority began broadcasting a rival, regionally-distributed, ITV service, supported by advertising. Nonetheless, the BBC was still regarded as the “high-brow” service, and was accorded perhaps-undue respect for that.

As regards engineering training, the reality for many years was that only the BBC offered any professional training. ITV’s contractors usually simply poached trained engineers from the BBC. Therefore, it seemed to me that the only way to get into broadcasting was to undergo the BBC’s training, and the only way to obtain that was to work there.

It turned out that I was wrong, on many counts.

It’s Not Licence-Payers’ Money We’re Wasting!

I began working for the BBC on 13th August, 1984. The location of my office was the so-called “Woodlands” building, which was at 80 Wood Lane, quite close to Television Centre in White City.

BBC Television Centre, as illustrated in the Ladybird book “How it works: Television”. The employee canteen looked out onto the “Blue Peter Garden”, which was located in the area marked “20” in the diagram. Copyright © 1968, Wills & Hepworth Ltd.

I went through the expected employee induction process, but, as I settled into the job, it began to seem that there was actually very little for me to do. Having asked to be assigned some work, I was given various unnecessary tasks, such as auditing the acceptance of a new audio mixing desk, which in fact had already been accepted. I was provided with no information about the expected performance characteristics of the audio desk, so my review was mostly meaningless anyway.

As I recall, the single highlight of that period of my employment occurred one day when we got an urgent message that a radio microphone had failed at Broadcasting House, a few hours prior to a live broadcast. I rushed over there with two colleagues to investigate, only to discover that a wire had come loose within the microphone base. We obtained a soldering iron, and (thanks to my EP1 training at Ferranti), all was fixed a few minutes before the broadcast! Seriously, that was as “cutting-edge” as things got!

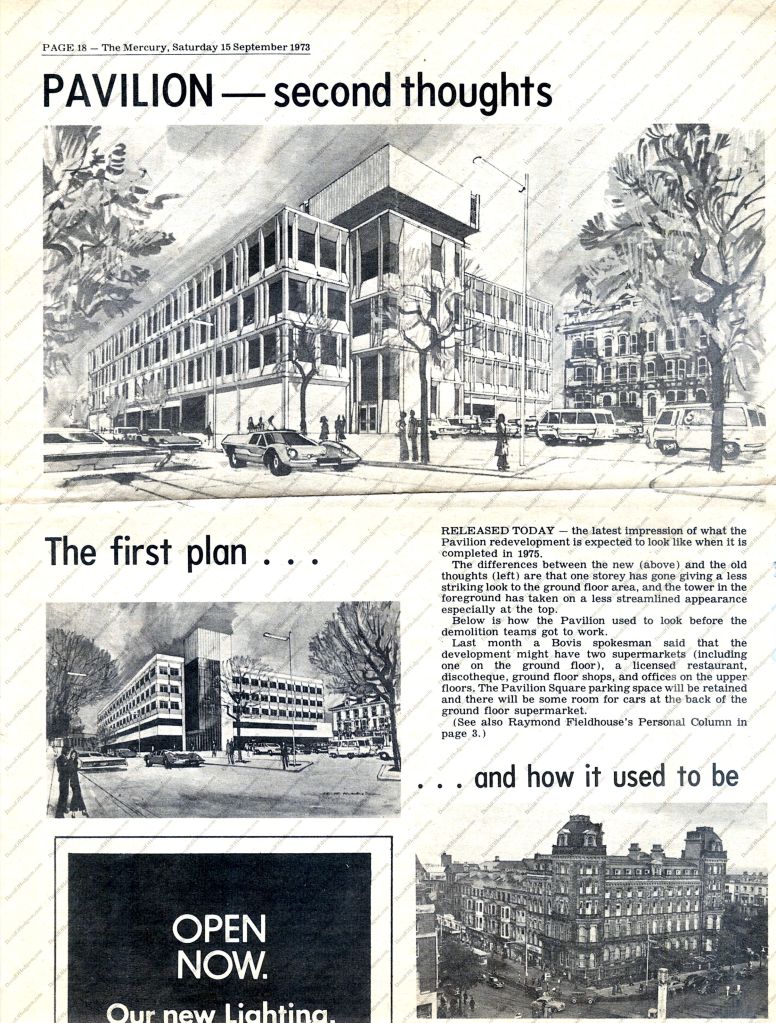

![South Elevation of Broadcasting House, from the book "London Deco", by Thibaud Hérem[20]. Copyright © 2013 Nobrow Press](https://davidohodgson.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/broadcastinghouse-1.jpg)

South Elevation of Broadcasting House, from the book “London Deco”, by Thibaud Hérem. Copyright © 2013 Nobrow Press

I complained to management about the lack of available work, but got nothing except shoulder-shrugging in response. Initially, they explained that it was because they had done me a favor by allowing me to start early, prior to the official training date at the Evesham training school. That excuse might have made sense, except for the fact that it was obvious that my fully-trained colleagues didn’t have sufficient work either!

I became disillusioned with the justifications that were being offered to me by SCPD management, and by what seemed to be a haughty refusal to engage with me. Having selected some of the best graduates from the best British universities, apparently they now expected those same people to accept seemingly illogical decisions without question! It seemed obvious to me that, despite their heads-in-the-sand attitude, they would not be able to maintain the charade indefinitely, and that the likely ultimate result was that at least some of us would be made redundant. The only remotely meaningful response that I ever got was, “Don’t rock the boat”. What “boat”? Why were my concerns about the true situation “rocking” anything?

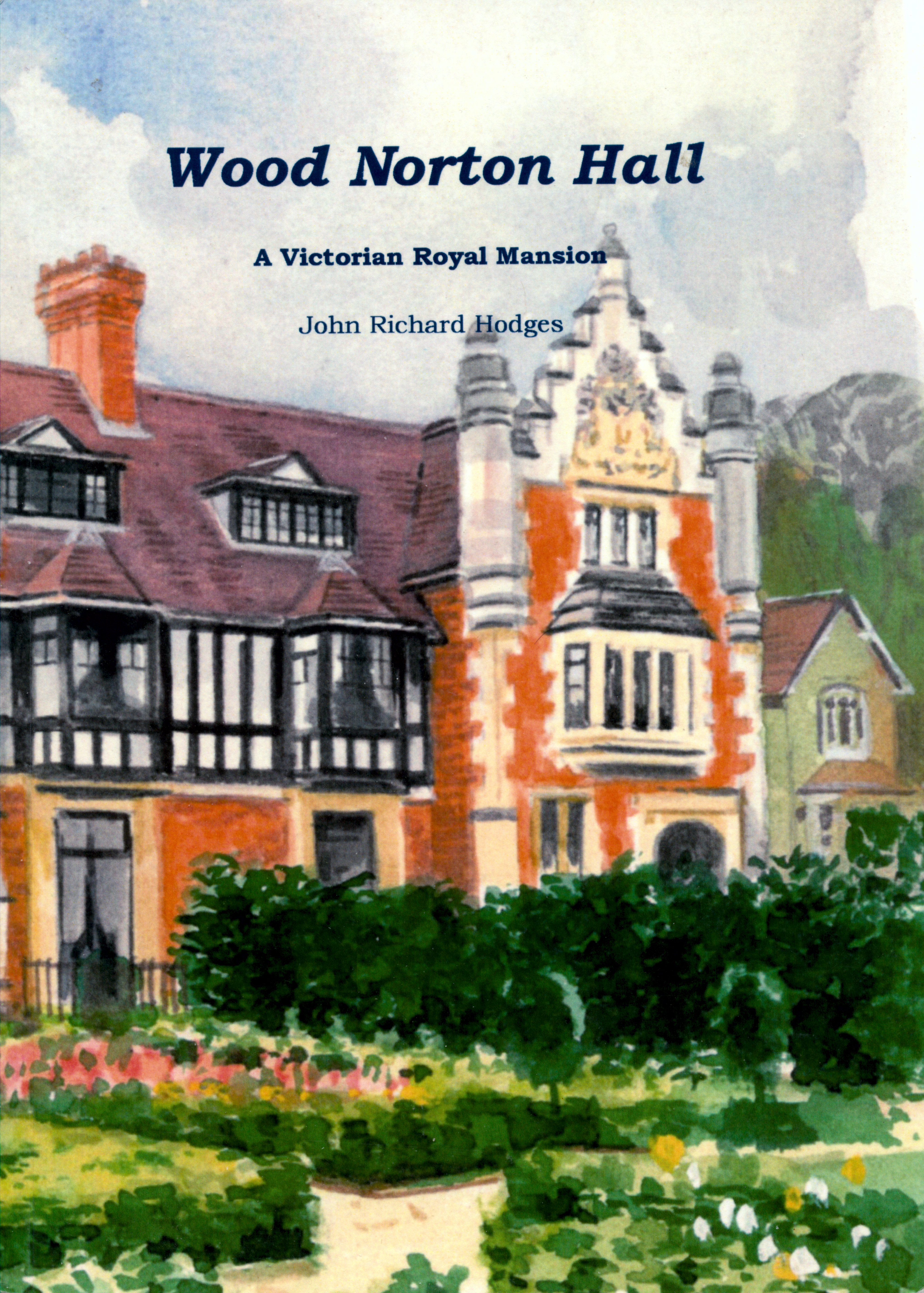

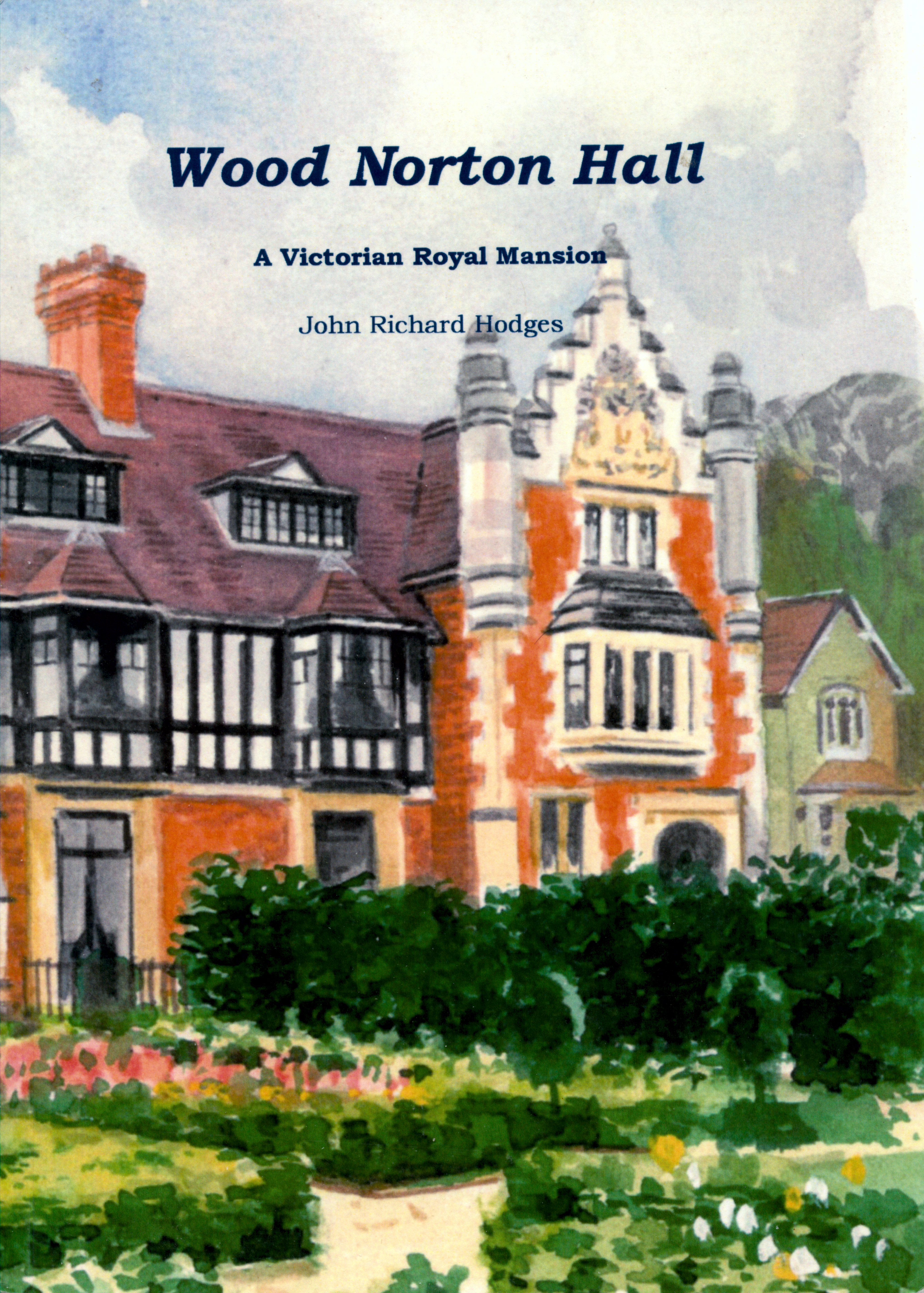

Following a few months of this tedium, I was sent along with many other new-hire engineers for the formal residential training sessions at the BBC Engineering Training School, which was located at Wood Norton Hall, in Evesham, Worcestershire (and which still exists, but is now a hotel). There is an entire book about Wood Norton Hall. It’s out-of-print, but can be obtained used, at, for example, https://www.amazon.co.uk/Wood-Norton-Hall-Victorian-Mansion/dp/0955405793/ref=sr_1_1

The cover of the book about Wood Norton Hall. Copyright © 2014 John Richard Hodges

As part of that course, we were required to undergo the EP1 training specified by the Institution of Electrical Engineers (IEE). As I mentioned in a previous post, I had already spent several months completing exactly that training at Ferranti, and had a certified notebook to prove it. Why, then, should I spend time redoing exactly the same training? When I asked that question, it became apparent that I was by no means the only new BBC trainee who had already completed the EP1 training.

I pointed out to management that forcing us all through the same training again was a serious waste of money. The BBC were always sensitive to the suggestion that they were squandering licence-payers’ money, so management was eager to defend their stance, with this appalling justification: “It’s not licence-payers’ money we’re wasting. The Engineering Industry Training Board (EITB) reimburses us for the cost of EP1, so it’s the EITB’s money we’re wasting!”

Wood Norton Hall as it appeared when I worked there. The upper floors had been destroyed in a fire during World War II, and never replaced! Copyright © 2014 John Richard Hodges

Sorry; Your Degree is too Good

At around that time, it struck me that the job I’d accepted at the BBC was not the role that I’d originally had in mind. My initial application, in 1980, had been for an “Operations” job, that is, as a technician who operated or maintained broadcasting equipment. Those were the kind of roles I’d noticed when I visited Yorkshire Television, and which had stimulated my interest in working in the field in the first place.

Therefore, I asked my manager whether I could transfer from SCPD to one of the Operations Departments. His astonishing answer to me was along the lines of, “Oh no. Those jobs are for people with third-class degrees. Your degree is too good for that!”

So, apparently I’d gone from being underqualified for the BBC job in 1980, to being overqualified for it in 1984!

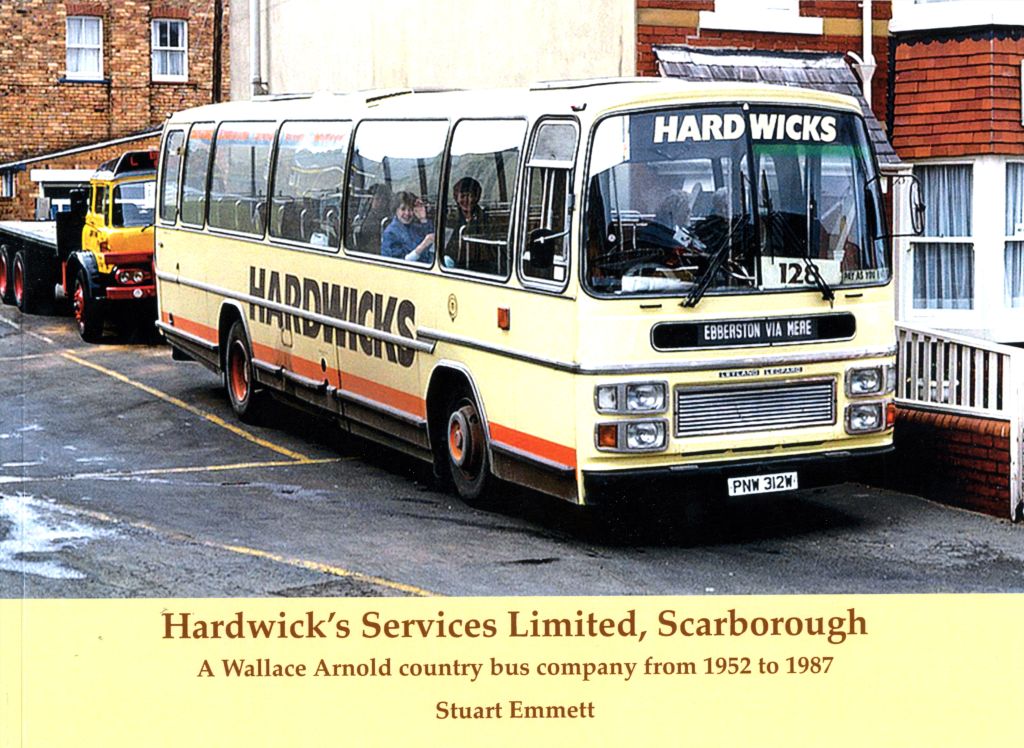

Having made no headway in trying to argue the problem with management, I eventually began looking for alternative employment, even if that would mean leaving the field of “video engineering”. After various interviews, I was offered an exciting position as “Technical Sales Engineer” by an electronics distributor called Swift-SASCO, who were based in Crawley, Sussex (but not in any way related to my previous employer, Swifts of Scarborough). Not only was the salary in that position comparable to what I was earning at the BBC, but they also offered an all-expenses-paid company car, plus the potential for sales bonuses. The offer was simply too good to ignore, so I accepted it and handed in my notice at SCPD, thinking sadly but mistakenly that that would be the end of my short career in video!

Retrospective: My Alternatives

Alternatively, I realize that I could perhaps have viewed my unproductive months of training at the BBC as being merely “paid education” and patiently plodded through it without complaint. I could also have spent my “enforced idleness” in exploring more of those historic buildings in which I found myself working. Perhaps I could then have moved to one of the ITV contractors? I’ll never know whether that would have worked out, but it would certainly have propelled the remainder my life in a very different direction, so in retrospect, I’m glad I did not.

In fact, I had overestimated the value of the BBC training. I’ve subsequently worked with many expatriate British engineers, quite a few of them specializing in video equipment design, yet not one of them ever underwent that BBC training! I discovered that the BBC’s engineering expertise simply was not held in high regard in the electronics or computer industries. As one former boss told me, “The BBC think they know it all, because they think they invented television. They don’t and they didn’t.”

After leaving the BBC, I stayed in contact with some of my former colleagues for a while. The word that got back to me was that, following my departure, management seems to have implicitly realized that the situation had been mishandled, and had made an effort to change their attitude. When one of my colleagues subsequently complained about some other unsatisfactory situation, his manager’s response was, “I’m glad you let us know. We don’t want anyone else to leave”!

I also discovered in the same way that, about six months after I resigned, many of my former colleagues were, in fact, made redundant from SCPD. My foreboding had been correct.

Why the Secrecy?

Nobody at the BBC ever offered me an explanation of what seemed to be the unreasonable behavior of SCPD’s management. Therefore, I can only surmise what was really happening at that time, based on descriptions and opinions I’ve received from other video engineers, inside and outside the BBC.

Here is what I was told:

Why did Studio Capital Projects have insufficient work?

As discussed in detail here, the then Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, and her Tory government, were engaged in a rather ridiculous ideological dispute with the BBC. The BBC (rightly) valued its independence, and its goal of providing objective, unbiased news reporting. Thatcher, on the other hand, took the view that, being funded by a licence fee, the BBC should in fact be a government propaganda arm. Unable to shut down or defund the BBC, she made petty attempts to hobble its position in other ways.

One such way was to insist that the BBC must “operate competitively”, supposedly to obtain value for money for licence-payers. Previously, whenever a BBC studio required refurbishment, the work had automatically gone to SCPD. Now, however, the BBC were forced to request bids for such work, not only from SCPD within the corporation, but also from external private companies.

The result was that external contractors always underbid, and so were awarded the contracts, leaving SCPD (which had bid according to the true costs of a project) without any work.

Logically, of course, if SCPD had no work, then the department should have closed or been repurposed. However, in that case, Thatcher would have won what was really a purely political battle, and some in the BBC were apparently determined not to concede.

Why did Studio Capital Projects hire more Engineers?

Given that SCPD had insufficient work for the engineers that it already employed, why would it nonetheless go ahead and hire even more engineers?

It was later suggested to me that this probably occurred because the BBC was “not a commercial organization”. Its annual income was essentially fixed by the licence fee collections, so the BBC’s budget was based on dividing up that fixed income among the various departments.

The primary way that a particular department could argue for a higher portion of the fixed budget was to employ more people. Hence, the goal of hiring more staff became completely detached from the question of whether such staff were actually needed!

Bad Times on the Horizon

The management issues that affected my employment at the BBC came as a great shock and disappointment to me at that time. Little did I realize back then that it would be just the start of a frustrating sequence of jobs with UK engineering employers, which would continue until I “escaped” to California (and relative sanity!) in 1987. Through no failing of my own, I worked for several employers during that 3-year period, with the management of each company being at best unstable, and at worst incompetent, as I experienced firsthand a portion of the terminal decline and failure of Britain’s electronics and computer industries. I hope to write more about some of those experiences in future posts.

It seems that the kind of mismanagement that plagued my employment experience in Britain is not a thing of the past. I was shocked by the recent news of the appalling Horizon Scandal in Britain, which seems to have stemmed from technical incompetence, and subsequent attempts by management to cover that up at any cost.

I am So Glad I Left

Let me emphasize once more that, in hindsight, I am so glad I quit that BBC job when I did! If I had not done that, but instead had listened to the discouraging comments of certain timid naysayers around me, and had clung on there, I would probably never have had the opportunity to move to California and work in “Silicon Valley”. As I have described in several earlier posts, there’s no question that the move to California changed my life immensely and permanently for the better.

I gave some thought to the wording of the title of this post. The phrase “illusory limitations” reflects both the way that I underestimated my own potential skills at that time, and the way that others attempted to impose false limitations on me. When I joined the BBC in that role, I really thought that it was the best I could do. I did not seriously imagine in those days that I could become a design engineer, and certainly not a patent-holding inventor. Fortunately, I didn’t ultimately settle for an underachieving career!

The message that I hope this tale of my experiences will convey to readers is not to be cowed by the unreasonable demands of any employer. Be confident in your own position, and don’t sacrifice your own future for the convenience of others who ultimately do not have your best interests at heart.

BBC Broadcasting House, from Portland Place

![South Elevation of Broadcasting House, from the book "London Deco", by Thibaud Hérem[20]. Copyright © 2013 Nobrow Press](https://davidohodgson.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/broadcastinghouse-1.jpg)