The drawing above, of Thorton Dale Railway Station, (reproduced much smaller than life-size here) was the most ambitious of the architectural views that I created for my Advanced-level Art project during 1977-78. I’ve also posted this drawing on a page about the subject – Thornton Dale railway station – along with several photos that I took, and sketches that I made, at the same time.

Not Part of the Syllabus

I realize that some of the illustrations that I’ve been reproducing in this blog from my Art study (such as this and this) may give the impression that architectural drawing skills were taught as an element in the A-level course. In fact, nothing could be further from the truth. My expertise in such drawing techniques derived entirely from an O-level in Geometric Drawing that I had completed at the Graham School a few years previously. During the two years of the A-level course, I don’t recall ever having been taught anything about architectural illustration!

A few years later, when I commenced my Student Apprenticeship at Ferranti, I naturally assumed that my Geometric Drawing O-level should count towards my training, but no! We were required to learn technical drawing as part of the IEE-prescribed EP1 training, but no credit was given for prior expertise in the subject.

Of course, the fact that I’d obtained an O-level in the subject did make the Ferranti training much easier to complete, so my prior qualification was useful in that sense.

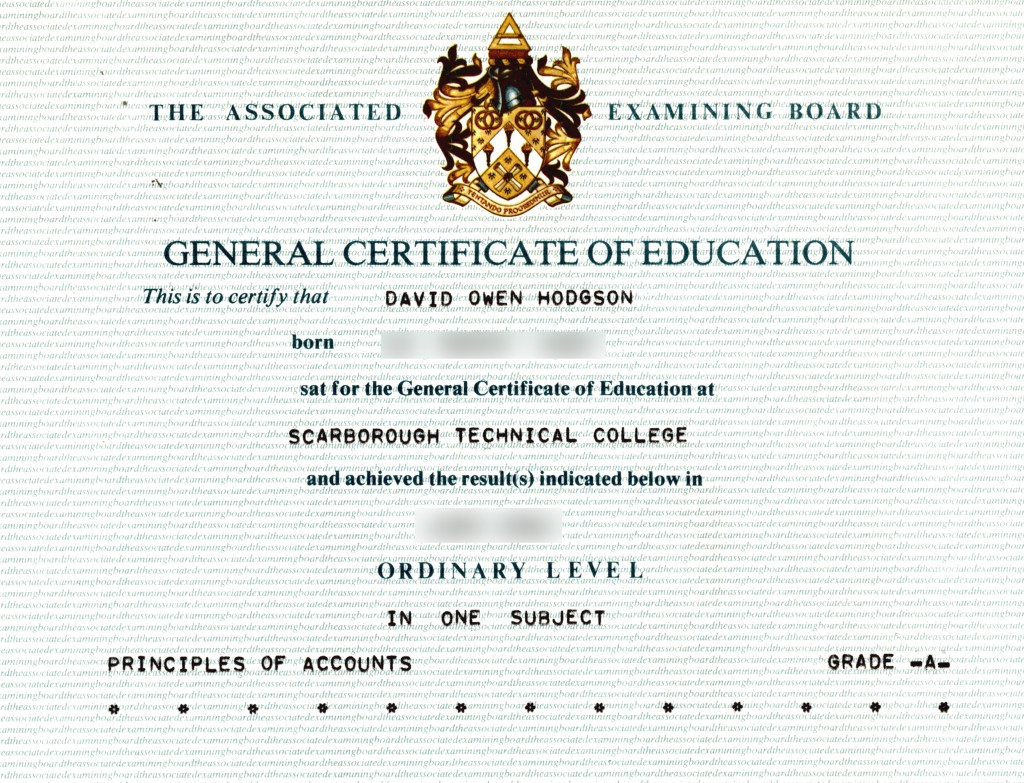

O-Level Principles of Accounting

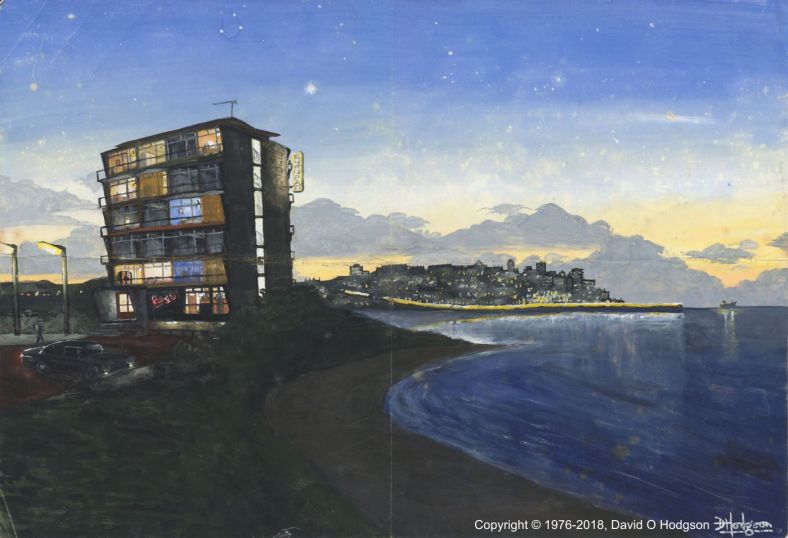

Here is another example of a qualification that I obtained, and which was useful, but was not recognized by professional bodies. As I’ve described in another post, prior to joining Ferranti, I had worked for about 18 months as a Purchase Accounts and Sales clerk at the light engineering company Swift’s of Scarborough.

Soon after my employment commenced, my manager suggested that I might consider obtaining an Ordinary-level qualification in Accounting. It seemed as though that would help me do my job better, so I started a course at the Scarborough Technical College (now Scarborough TEC). I sat the exam and easily obtained the O-level in 1980. There was some suggestion that I should continue by taking an Advanced level qualification in the same subject, but, by that time, I had concluded that my time would better be spent studying to return to university. I already had more than sufficient O- and A-levels to qualify for university entry, so why add another one?

Useful in my Job

There’s no question that what I learned from the O-level course did prove useful in the execution of my duties at Swift’s. Perhaps the most basic principle instilled into us by the course was the concept of double-entry bookkeeping; a simple idea but a powerful and necessary one. The only problem with the O-level qualification was that it was not professionally recognized in any way; had I wanted to become a Chartered Accountant, my O-level would not have been considered as a contributing qualification.

That leads to a seemingly-obvious question: Why didn’t Swifts encourage us to get recognized professional qualifications? At the time, I suspected that the cause may have been my manager’s lack of such qualifications; he had only an A-level in Accounting, and that also was not recognized professionally. Presumably, he would not have liked the idea of his subordinate becoming more qualified than he was! With the benefit of hindsight, however, I suspect that the real cause had more to do with the inherent sexism of the time and place. The underlying assumption of Swift’s management was that whoever they hired for any Accounts Clerk position would be a young woman, with a few O-levels, and perhaps a couple of A-levels. The young woman could be expected to work at Swift’s only for a few years before getting married, at which point (they assumed) she would leave employment forever to become a housewife and raise children. As such, presumably Swift’s management saw no point in expending time and money on professional training for a career that their employees would probably never have.

Of course, in a more competitive employment environment, Swift’s would probably have been forced to offer proper professional training, to attract candidates with sufficient intelligence for the job. However, the sad reality was that there were so few opportunities for intelligent young people in the Scarborough area that they didn’t need to.

Useful at University

Having left Swift’s, and embarked on my degree course in Electronics at Imperial College, London, I discovered that we were encouraged to take non-engineering courses such as Accounting & Finance, Macroeconomics, etc. Again, the fact that I’d obtained the Principles of Accounting O-level made my Imperial College studies in Accounting & Finance much easier to grasp, so the knowledge I’d gained did come in useful again, even if it was not professionally recognized. My results in the Accounting & Finance course counted towards my final degree grades.

They still don’t seem to get it

More recently, it has seemed to me that, at the very least, Ordinary-level Principles of Accounting would have been a beneficial subject for study by those who designed the Horizon software for the British Post Office!

As the forensic accountant investigating that scandalous failure reported, the software violated basic principles of double-entry bookkeeping, such that, even if the code had been well implemented (which it was not), the system was bound to fail quite quickly.

Can it be that not one of the technical contributors to the Horizon software system had even an O-level in Principles of Accounts? If so, then how could a major national institution such as the Post Office ever have believed that the resulting system would be trustworthy as a key component of their accounting systems? I don’t know the answers to those questions, but they would certainly seem to be worthy of investigation!