Jewry Wall & St. Nicholas’ Church, Leicester, in 2008

I’ve never lived in Leicester, UK, but, about 30 years ago, I found myself visiting the city quite frequently. Leicester’s city motto is Semper Eadem, which means “Always the Same“, but, when I revisited the city almost thirty years later, I discovered that the motto is not accurate!

Although superficially just another of England’s many formerly-industrial Midlands cities (and now a very multicultural city), Leicester hides some historical gems and national treasures. One such treasure is the Jewry Wall site, shown above, which is a substantial remaining relic of the city’s Roman origins, and is in fact the second-largest remaining Roman structure in Britain. Next to the ruins of the Roman baths stands St. Nicholas’ Church. The idyllic scene in the photo belies the fact that this site is actually in the middle of the city, adjacent to the busy inner ring road.

Of course, in 2012, Leicester shot to worldwide fame due to another unique treasure, when it was confirmed that the long-lost body of King Richard III had been discovered under a car park in the city center. For centuries, the accepted view had been that Richard’s remains had been thrown into the River Soar some time after he lost the Battle of Bosworth in 1485, and thus were lost for ever.

The photo below, taken during my October 2012 visit, shows the trench in the car park where Richard’s remains had been found a few months earlier. At the time that the bones were interred there (presumably in 1485), this site was part of the monastery of Greyfriars. The spire in the background is that of Leicester Cathedral.

Trench in which the remains of King Richard III were found, Leicester

Industrial Decay

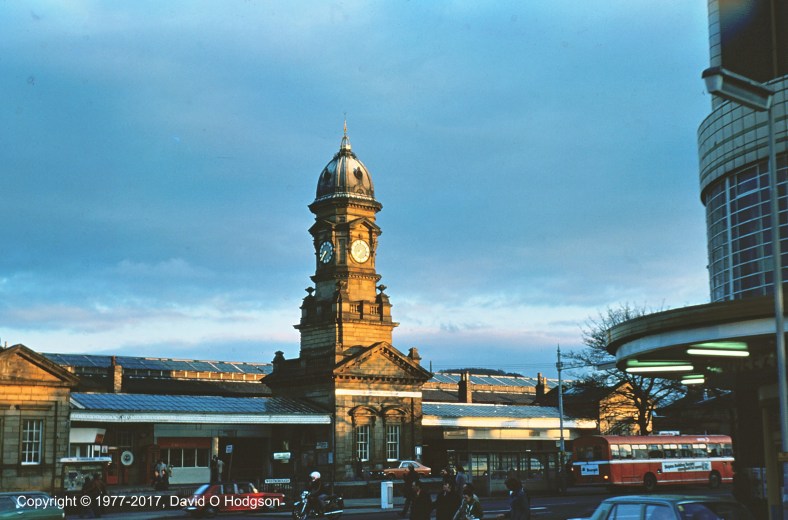

I first visited Leicester between Autumn 1978 and Spring 1979. Thinking back to those early visits, my memories of the city conjure up a dark and grimy maze of damp streets, derelict railway lines and dilapidated businesses.

In those days, one of the most imposing industrial relics was the immense blue brick viaduct built in 1899 for the Great Central Railway, whose new main line had been pushed through the west side of the city center at huge expense. The viaduct was called the “West Bridge Viaduct”, which is not the strange name duplication that it seems, because the viaduct actually spanned not only the River Soar, but also the West Bridge itself. The West Bridge is a road bridge at the site of a river crossing, which has existed there since at least Roman times.

The Great Central line was built as part of a grand scheme to connect the manufacturing centers of Northern England with Europe via a Channel Tunnel, but of course the tunnel wasn’t built until much too late for the railway, and all those manufacturing industries. After much vacillation and ineptitude, British Rail finally closed the Great Central main line in the 1960s, making the viaduct redundant.

When I visited in January 1979, demolition work was underway on portions of the viaduct that had spanned the West Bridge and the River Soar.

The photo below, looking north towards the river, shows the remaining abutments, after the iron spans had been removed. A Leicester City Transport bus glints in the evening sun as it traverses the roundabout.

West Bridge Viaduct, Leicester, January 1979

A second photo taken on the same date, from the other side of the river, shows the dome-like decorative abutment of the West Bridge, amid a clutter of half-demolished buildings and muddy roads. The isolated abutment of the former railway viaduct is in the center of the view.

West Bridge, Leicester, January 1979

And Nearly Thirty Years Later…

I didn’t return to the city until the Spring of 2007, and, when I did, I decided to try to revisit some of my “old haunts”. I headed to the West Bridge, which was easy to find, but when I tried to relocate the spots from which I’d taken the 1979 photos, I found myself completely disoriented.

I’d realized that the West Bridge Viaduct would by now have vanished completely, but in fact almost everything else seemed to have been remodeled too. There was no trace of the roundabout that had featured in my earlier photograph.

It turned out that the main source of my confusion was that a second road bridge had been built alongside the old West Bridge, so that it now forms part of a dual-carriageway system. The photo below shows the two parallel bridges from underneath, at the level of the River Soar towpath, with the old bridge beyond the new one. The weed-topped river wall on the far left formed part of the viaduct abutment.

Leicester, West Bridge from River Soar

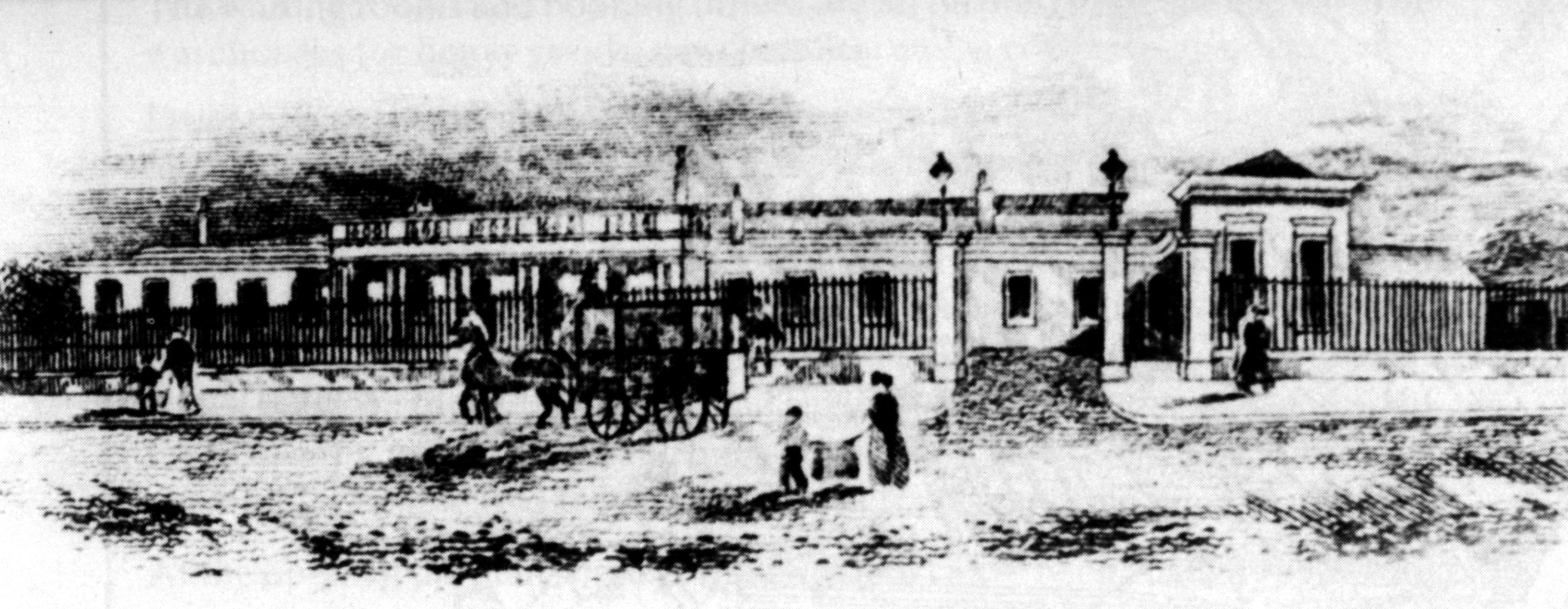

The Grandeur That Was Ratae Corieltauvorum

The Roman name of the settlement that developed into modern Leicester was Ratae Corieltauvorum. Leicester was one of the first cities in Britain to take proactive steps to preserve its Roman heritage. The Jewry Wall ruin itself has always been obvious, but the foundations of the Roman bathhouse next to it were only discovered during the 1930s. Instead of building over them, Leicester Corporation cleared the site and opened it to the public.

Recently, as part of the preparatory work for a fictional story about Leicester in the 1960s, I produced the pencil sketch below, showing the wife of the story’s protagonist sitting on one of the Roman walls near the Jewry Wall, with St. Nicholas’ Church in the background. The woman in the picture doesn’t exist, of course, but the structures in the background definitely do.

“Jeannie at the Jewry Wall”

For the holiday season, here’s a slightly different “throwback” article.

For the holiday season, here’s a slightly different “throwback” article.

I just finished reading this excellent book:

I just finished reading this excellent book: