St. Pancras International Station, London, 2010

In 2010, I visited a spectacularly transformed St. Pancras Station in London, for the first time since I had lived in the city. In the photograph (below) taken during a 1981 visit, St. Pancras was a dowdy, run-down relic, the only possible future for which seemed to be closure and demolition.

St. Pancras Station, 1981

But, thankfully, it was not to be, partly due to the efforts of one man, and instead, the huge Victorian edifice was not only saved, but was transformed into the impressive, functional St. Pancras International Station. The photograph below shows the beautiful and airy interior of the trainshed of St. Pancras International, on a day when a German ICE train was visiting to promote future usage of the station by DB.

Interior of St. Pancras International Station, 2010

Although the redevelopment of St. Pancras is one of the most internationally famous triumphs of architectural rehabilitation, there have been many other examples of success and failure.

Yesterday, someone posted on the Facebook page of my alma mater, Imperial College, a photograph of the Imperial Institute, which was a predecessor building in South Kensington, the site of which is now occupied by Imperial College. That reminded me of the many heated battles that have occurred during my lifetime over architecture, and the demolition or redevelopment of buildings. In the past, the usual result was demolition, but, during the past twenty years or so, more enlightened thinking has prevailed, resulting in such wonderful renovations as St. Pancras.

During the 1960s (long before I became a university student), the Imperial Institute building was the focus of a heated dispute between those who wanted to demolish the Victorian edifice completely, and those who wanted to preserve it.

The redevelopers of the Imperial College campus wanted to sweep away all the Victorian architecture and replace it with what they considered to be modern and functional structures.

However, an organization called the Victorian Society, led by the poet Sir John Betjeman, fought for the preservation of Victorian architecture, and became particularly involved in the Imperial College plans. Although they were not able to save everything, the Victorian Society won a partial victory in that case, and managed to force the developers to retain the central tower of the Imperial Institute, which, as a freestanding building, was renamed the Queens Tower, as shown in my 1981 photograph below.

Queens Tower, Imperial College, in snow, 1981

Now, whenever anyone needs a general photograph of “Imperial College”, you can be fairly certain that they’ll choose a view that includes the Queen’s Tower. The sad reality is that most of Imperial College’s modern architecture has very little character, and the Queen’s Tower has become a de facto icon of the college. (Incidentally, the tower is not the only pre-1960s architecture remaining on the Imperial College campus. For example, the original City & Guilds College building still survives on Prince Consort Road. However, that structure is relatively undistinguished and squat, as you can see in this current Google Streetview.)

I must admit that, while a student at Imperial College, I myself was responsible for heaping further derision on the Queens Tower. As part of a spoof Felix article about the stationing of US troops within Imperial College, I contributed the illustration below, showing how the Queen’s Tower was to be converted into a launch platform for cruise missiles! (“Felix” was and still is the Imperial College student newspaper, tracing its roots back to the days when H G Wells was a student at the college.)

Queens Tower Missile Installation, 1983

Betjeman and the Victorian Society were also instrumental in frustrating plans for the demolition of St. Pancras Station, which preserved the building for its eventual renovation. Appropriately, Betjeman’s contribution has been commemorated with a statue of him on the platform at St. Pancras, as shown below.

Statue of Sir John Betjeman at St. Pancras International Station

Personally, I don’t regard “high Victorian” architecture as being the epitome of good taste, but surely it is preferable to characterless, badly-constructed concrete boxes that replaced so much of it.

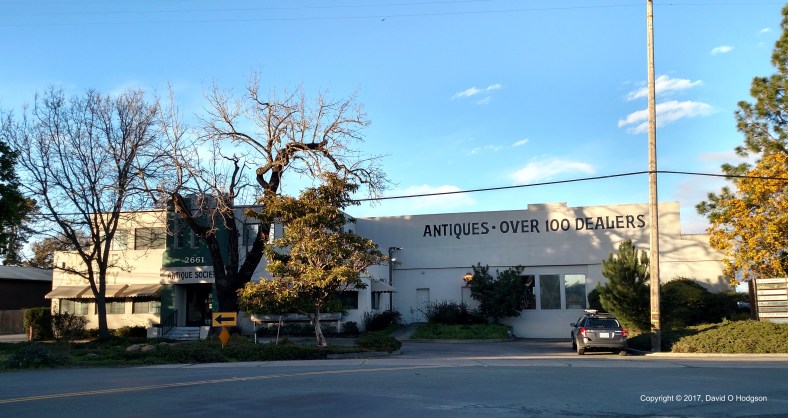

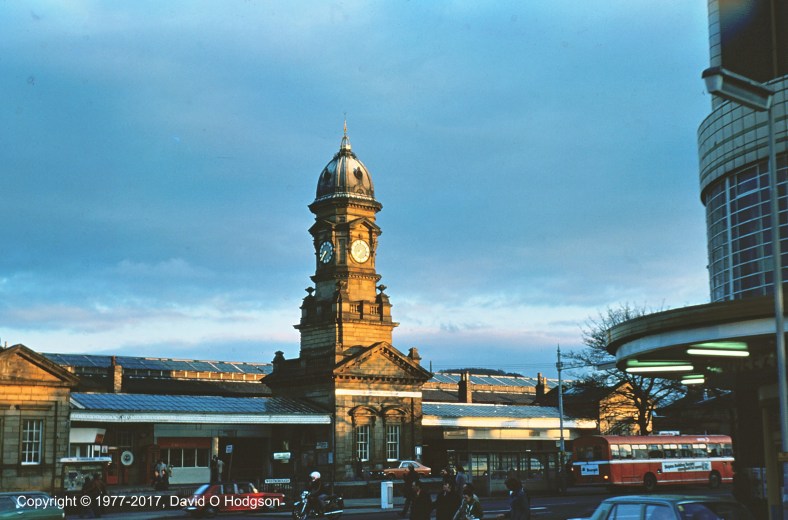

In a previous post, I showed how the architecture of Scarborough Central Station was redeveloped from the simple neoclassical design of 1845, to the ornate high-Victorian “wedding cake” that still survives today.